PHILIPPE RUAULT: ARCHITECTURE AND PHOTOGRAPHY

BY SUSANA VENTURA

SUSANA VENTURA: Do you think photography is able to represent the lived space of architecture? If so, how can it do it? Or, more generally, how would you describe the relation between photography and architecture?

PHILIPPE RUAULT: For me, it’s pretty clear that photography may represent the space. All it takes is simply getting “la bonne distance” (the right distance) between the self and architecture, the architect. But architectural photography is changing so quickly. Does it still exist?

SV: How do you find that “bonne distance”?

PR: Immediately, spontaneously, but after having thought about the architectural pro- ject: the correct rapport between me and the architectural object.

SV: What leads you to take a certain photograph? Or what makes you opt for a certain composition, frame, and luminosity, instead of others?

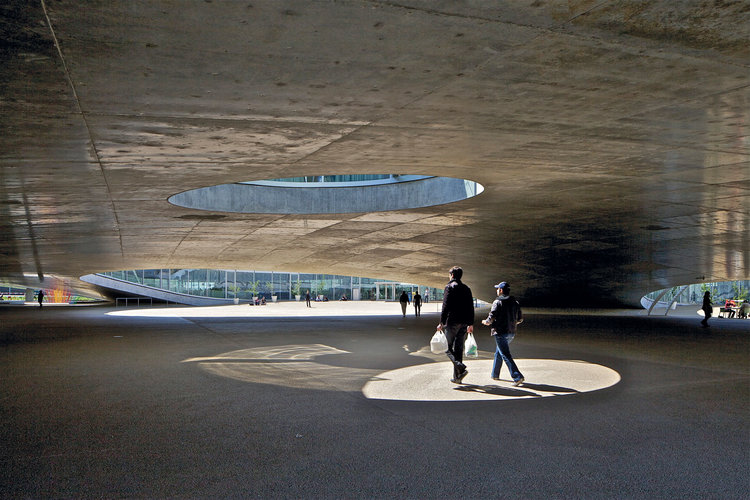

PR: Architecture and the building work altogether as a coherent whole, an open space both to the exterior and the interior. Architecture is in a state of absence, it is in between the world, nature, and the inhabitants of the place. Photography is in the center of all that like a carrier, a passerby. My photography must express that emotion.

SV: Do you believe that emotion belongs to the work of architecture and can your photographs extract it, allowing us to experience the same emotion through the photograph? Or the emotion we perceive through the photograph is another kind of emotion, one that you have composed (because photography is not the indifferent medium that we sometimes think of; it produces space and fabricates emotions)?

PR: I think that the observer runs through all these different emotions and lives his own emotions according to his culture, his experiences.

SV: When we look at your photographs of the different works of architecture built by various architects, we are immediately sent back to their work. For instance, in your photographs of Jean Nouvel’s work it is common to find a photograph playing with reflections. Immediately, we think of how Jean Nouvel usually plays with the real and the virtual in his buildings or when he adds several layers to generate an ambiguous perception of the real. On the other hand, we also easily perceive your own elements of composition: you don’t use reflections in a traditional way, sometimes you introduce both time and movement in the photograph (such as in that beautiful photograph of the Minneapolis theatre interior), you use color in a very specific way (usually as light)...

What do you think about the relation between the different works of architecture, the different architects that have designed them and your own ideas of photography?

PR: Firstly, it is about understanding the project and how it is formally done. Then photography must have its own means (and the photographic one translates this form). The photographer is a “carrier” who has the privilege of living the experience directly and the possibility of providing it with a form.

SV: What is the role of desire in your work?

PR: What you need is not a particular kind of desire, just the need to feel up for everything: what is there, what may arrive without being judgmental. To feel good in your body and in your head.