A sausage has two ends. Dieter Hammer in conversation with Bastien Rousseau

Dieter Hammer (Munich, 1969) is an artist, philosopher, kendoist and archer currently living in Bavaria, Germany.

The following interview discusses the affective semiotic potency of Architecture Photography in an era of sign-consumption and its ability to bring awareness and possibly any change into people’s daily life. It was conducted through emails and then edited in order to enrich and smoothen your reading experience.

-

Bastien Rousseau: Considering that humans' cerebral plasticity could be evolving towards a higher visual sensitivity in a digital world of image and sign consumption, do you foresee how Photography still could be potent amongst such a white noise?

Dieter Hammer: Would not it be rather that the human brain gets saturated with awhite noise of digitally accessed images?

Bastien Rousseau: Apparently, as a result of this tremendous intake of sign-images and visual information of all sorts and specially through the use of screens, our neural plasticity to 'whirl-downgrade' to a more reptilian version where most activity locates itself in the lower rear cortex. In the context we are describing here, one may wonder what Photography still has to offer...

Dieter Hammer: This is fun. I would not see it so dramatically though. The human brain is well able to filter out irrelevant information. It would not be possible for us to survive otherwise. Reducing complexity is a common way of dealing with it. Most people that I know are still fine... ! Of course, Photography may help (re)framing and alleviate complexity so that it may improve their ability and will to cope with it.

Bastien Rousseau: I remember you telling me that you once were a painter. How did you start working with photography then?

Dieter Hammer: At the time I was painting, I remember that I did not really like photography. I always felt that the camera prevented me from experiencing the present moment. With painting, I was into creating. Photography was for me only about recording. It actually was way more restricted when I grew up than it is today with the digital.

I started to experiment with digital photography in the mid-nineties. However, most of my early serious photographic work was based on analog film. I chose analog photography over digital exactly because of its restrictions. It did provide the resistance I needed to creatively ‘maneuver around’ and find new ways of approaching photography. My goal had become to make a photograph rather than simply take one.

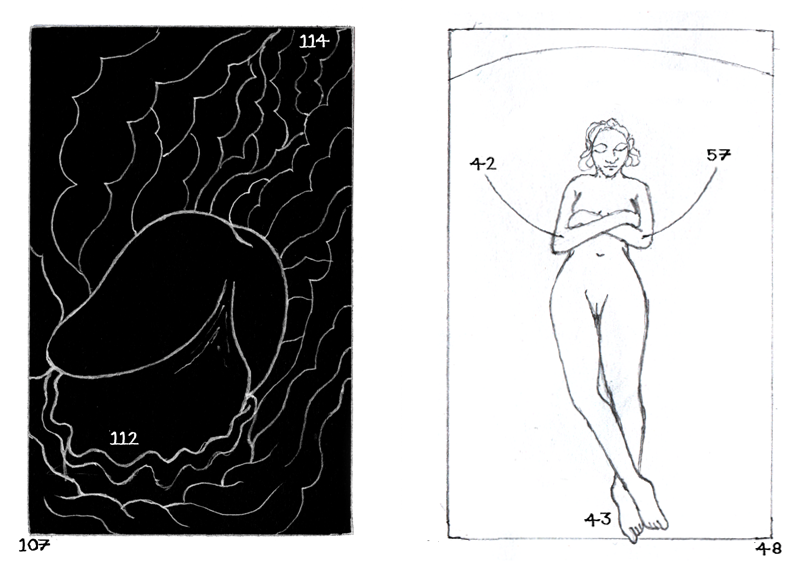

In this regard, a decisive event occurred in 2011 when I forgot to rewind the film roll and opened the camera by mistake. Thus, light leaked in and overcast parts of the recorded images. This led path to further researching the ontology of the image through a ‘transmimetic’ understanding of photography.

Bastien Rousseau: I understand that when photo particles get inside the camera and interact with the film, something similar to what you would like to happen when you are ‘taking’ a photograph with the intention to do so through the lens of your camera does happen with no intention of yours: it just does. This event not only cancels any possible sense of truthful ‘representation’ of what has been captured thus but also makes one aware of the physical actuality of light as a constitutive and overwhelming element of one’s everyday.

Funny it is to consider (shooting/capturing) directions when thinking of analog photography: could the photographs you had taken that day be Cubist-like to some extent, sharing different perspectives flattened on a single plate?

Dieter Hammer: It is interesting that you mention Cubism in this context. Indeed, Picasso used photography as a source of inspiration. What happens when someone sat pausing moved while being shot was known to him. Film was slow at that time, and exposures used to take quite some time. Eadweard Muybridge’s photographic studies of motion were pretty well known. Anton Giulio Bragaglia’s Photodynamism is worth mentioning here too. Well, it is something rather inherent to Photography and I guess that Cubists simply drew inspiration from it. It is an aspect of Photography that has been forgotten while striving to improve the mimetic performance of photographic apparatuses. That is one of the reasons why I was pondering on its ‘employment’ in various multiple ways; not so much with Cubism in mind, but pondering the question: is there more to Photography?

Bastien Rousseau: In 2014, you have been involved in an event titled Positionen der Aktuellen Architekturfotografie. Could you tell us about it?

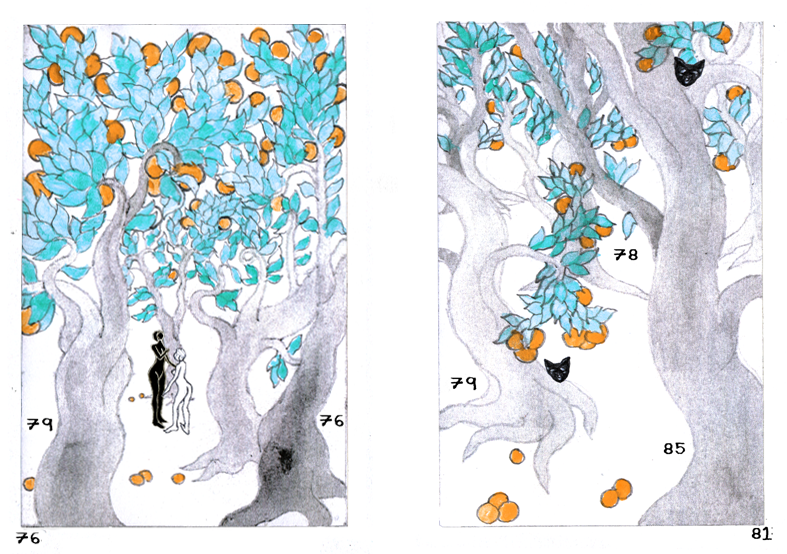

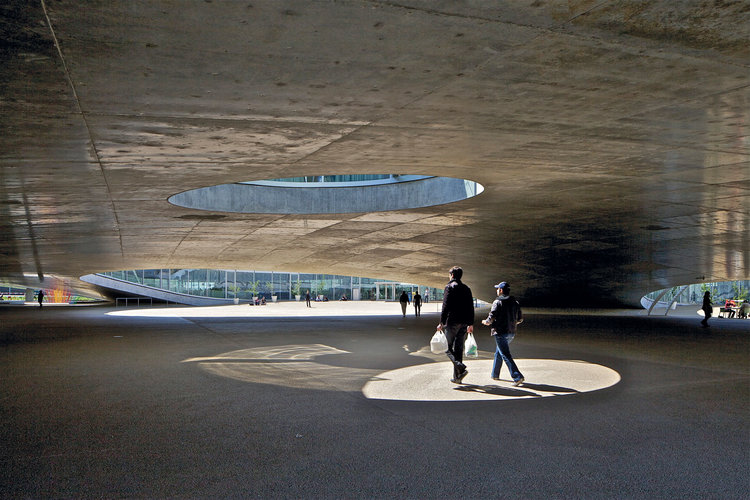

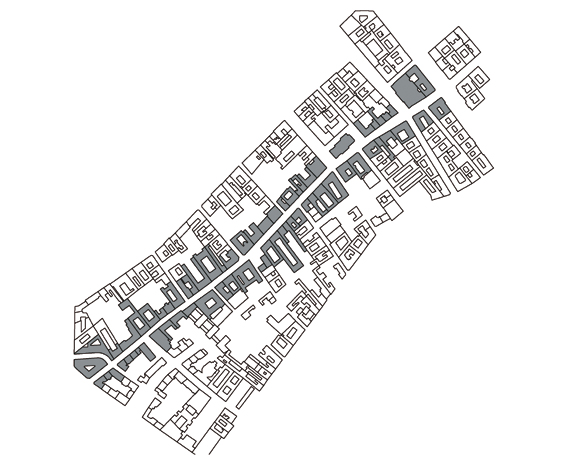

Dieter Hammer: Sure, it was an exhibition about current trends in Architecture Photography curated by Dr. Barbara Wolf at the Architecture Museum of Swabia in Augsburg. My contribution was a a series of ten minute-long ‘exposures’ of the village of Seysdorf’s architectural structures which I took in a cold winter night. A long exposure records light emissions that come and go during its process. What is otherwise sequential in film can be seen compressed in a single photograph. You can see the buildings and everything that emitted light as traces of life inside and around the architectural structures.

Bastien Rousseau: I should be curious to know what may be so crucial about Architecture Photography. Could the point be showing the pictures so that people may become aware of something, in general or in particular? Could there be more to it, in public space for instance?

Dieter Hammer: The challenge in Architecture Photography would be to get the proportions right. Therefore you need a view camera. My approach was the exception, maybe because I did not have Architecture Photography in mind when I took those photographs! I guess you could say that there are two main approaches towards it. One is strictly representative: Architects need good documentation of their work to share it through different media. The other one seeks to incorporate architectural structures into a creative concept. Of course, it could also be a mixture of both approaches. The exhibition was about juxtaposing a given variety of methodologies, dealing with architecture in different ways, from formalistic to conceptual.

Bastien Rousseau: Perhaps you could tell us about the scenography of that exhibition and whether curatorial issues were discussed with the exhibiting artists beforehand.

Dieter Hammer: Curatorially speaking, it mainly was a question of choosing photographers with different methodologies and whom had been known to the museum and arrange ‘samples’ of their work across its rooms. Each of the exhibited photographers wrote a text explaining their work relationship with architecture. Dr. Wolf made her selection of works based on personal criteria together with the photographers. I did appreciate that very much.

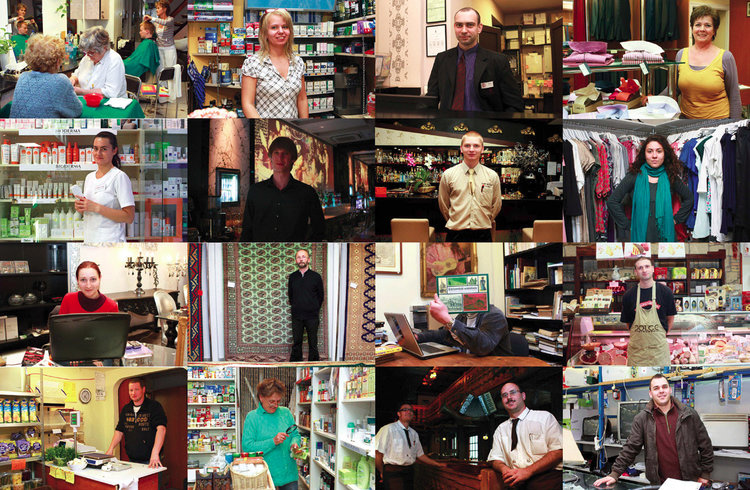

Long before the exhibition, we had been discussing one of Julius Shulman’s photographic series on architect Richard Neutra’s Kaufman House (Palm Springs, 1947). My Seysdorf series was partially inspired by this particular work of his. In Shulman’s, I particularly like that he often places people around or inside the buildings he means to photograph. Thereby, he sets a contraposto to the dominant functionalist approach embraced by his peers.

Architecture is a journey, not a destination: it serves life with a purpose. It is not an end in itself. In my Seysdorf series, the human presence was enacted by light trails caused by domestic human activity while the human figure was rendered invisible. I think, these traces of life are important.

Bastien Rousseau: Why did you choose to expose your film during 10 minutes?

Dieter Hammer: Around 2011, I used to experiment a lot with analog film photography. In this series, I was going for the particular atmosphere which a longer exposure happens to create. You get subtle motion blur around the static elements, upsetting light emitted by objects, like cars, and let them behave as hazardous light painting devices. People turn on and off light in their houses, etc. I chose a few very cold winter nights when temperatures went down to -10°C. I read articles on long exposure photography and came across photographers like Eugène Atget and his Paris series, Todd Hido’s ‘house hunting’ series, Michael Kenna’s long time night exposures and of course Julius Shulman’s dramatic shot of the Kaufman House in Palm Springs. On the account of what I had read then, I thought that ten minutes should be working fine. I shot at f11 with a hyperfocal setting using medium format film cameras.

Bastien Rousseau: This was before The Cosmic Artisan exhibition in London (Siegfried Contemporary, 2013) and the reflection that came alongside, on photographs being neither solely mimetic nor non-mimetic but potentially both depending on the scale one considers them: quantum, atomic, molecular, pictorial. How did this comprehension of theimage's ontology change your approach towards photography?

Dieter Hammer: You are right... A sausage has two ends, yet there is a sausage in between.

My approach towards Photography is a holistic one, where the exhibiting apparatus is as important as the end photograph’s content. For example, the edges or the frame (if so) of a printed photograph necessarily affect the viewer when s.he enters in relation with it. I like to consider such kind of ‘detail’ to create circumstantiated aesthetic experiences. Actually, this has allowed me to no longer stick to the use of photography to create those experiences. It has been a few years now that I am using a performative mode to convey similar notions, such as Duchamp’s ‘inframince’ and Photography’s necessary ‘transmimetic’ nature.

Bastien Rousseau: It sounds as if art making would have to be a matter of conscious and deliberate experience crafting, which entails that one's focus should be on the actual experience of a given group of people rather than on aesthetic production. I sense that there may be a way one could reduce the level of contingency at play, possibly by mapping out combinations of affects with multi-sensorial (aesthetic) elements... In other words, if our direct environment constantly is affecting us and our decisions and ways of handling it, life is the ultimate aesthetic experience.

Thus, as art making is rather about hacking the actual by introducing other, or (in quantum terms) ‘new’, information to actual configurations and face people with such alternatives, however much less in conceptual terms and certainly more in terms of affective semiotics. I guess Digital Marketing and Marketing Research already are a few steps ahead on this. The art world's hypocritical inherited leftist moralistic refusal to take on the enemy's tools, no matter potent or not, prevents it from effectively change our world's harmful habits.

Dieter Hammer: I pretty much like ‘conscious and deliberate experience crafting’! Indeed, art is a matter of life and certainly is not alien to it. As a matter of fact, do you rememberit, the brief, intense movement I used to perform with my hand to call for one’s attention on those scales of perception, through imagination? I performed it to artist Kentaro Yamada on Siegfried Contemporary showroom’s coffee table. He asked me for how long I had been practicing Kendo (Japanese sword fighting) because of the intense energy he could sense in my hand.

Photographs © Dieter Hammer

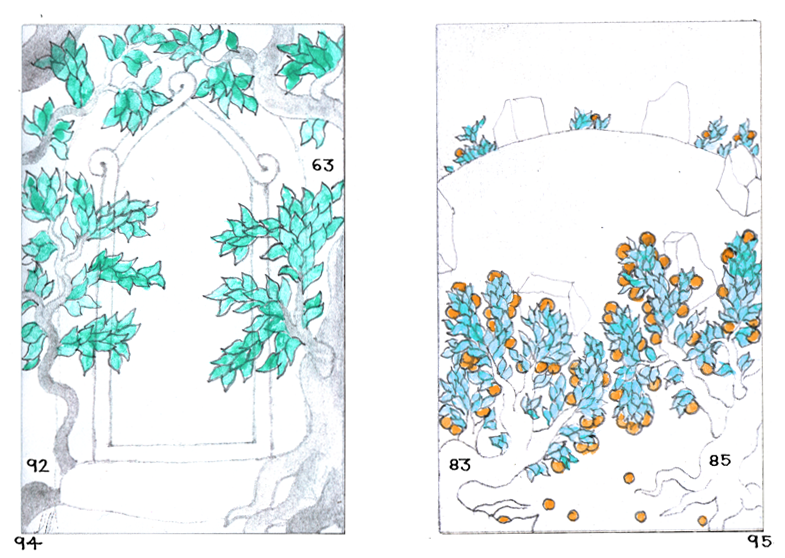

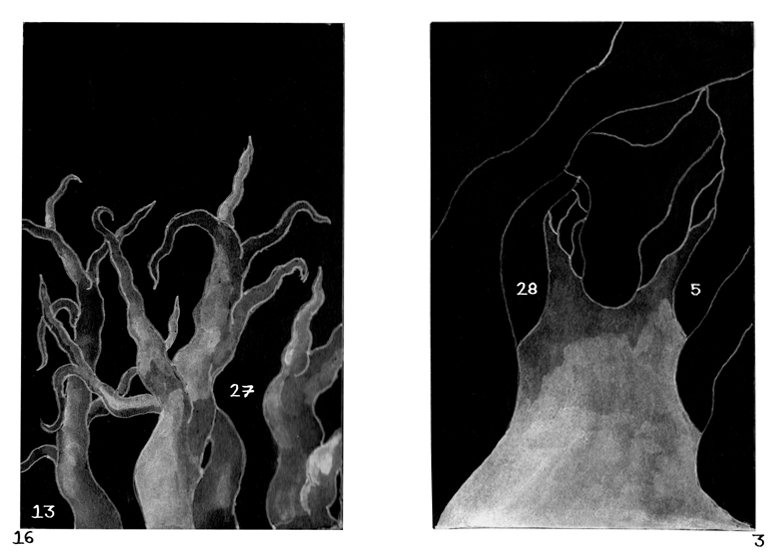

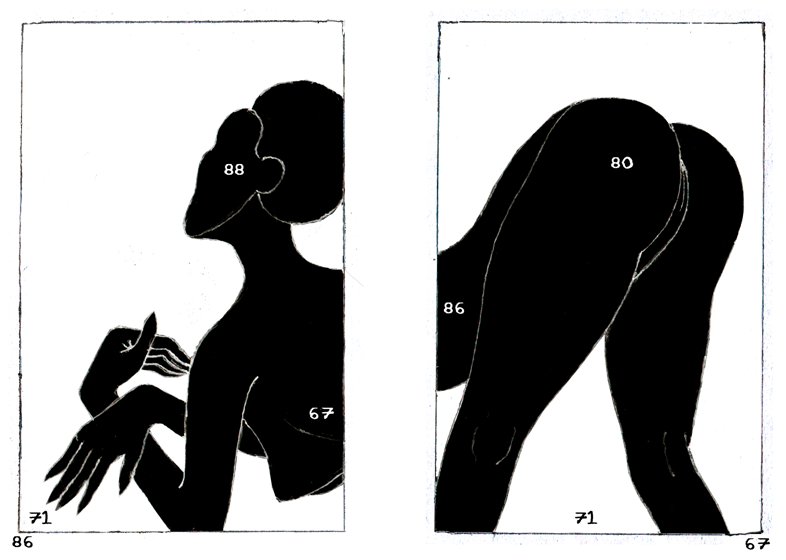

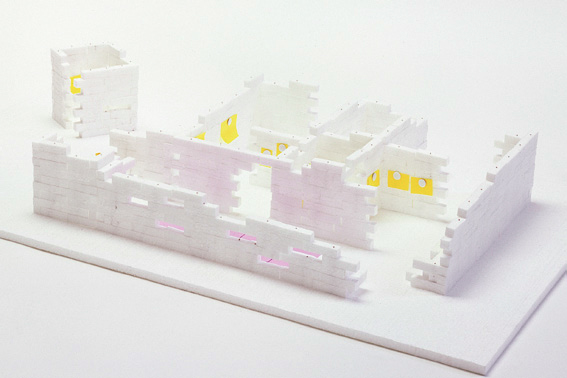

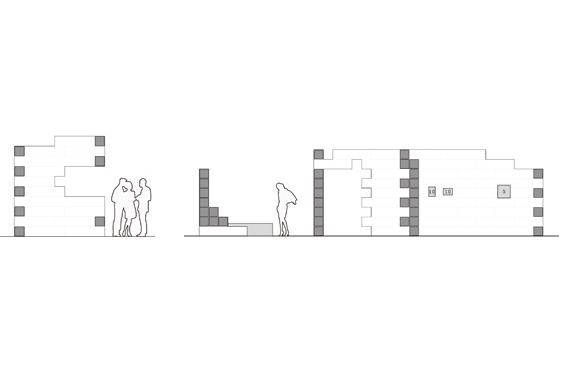

> first image: installation view, Forest near Seysdorf, 2014

in Mulligan Stew, curated by Bastien Rousseau,

5UN7, Bordeaux, 2014

> next four: Seysdorf series, 2011

> last image: installation view, Image Generator, 2013

and Laserluminogramme, 2012

in Lumen - Amen, Transformationen des Lichts,

curated by Dr. Benjamin Kummer and Katja Böhlau,

Friedhofsmuseum, Berlin, 2016

Hammer’s work currently focuses on the mediation of Beauty and Meaning through Installation, Performance and Photography.

For more information, please visit www.beyondwhitenoise.de

Bastien Rousseau is a cosmic artisan based in Tours, France whose current work and research focus on everyday situations as a non-finite semiological affective experience.