EMERGING PORTUGUESE PHOTOGRAPHER MIGUEL REFRESCO

BY JIÔN KIIM

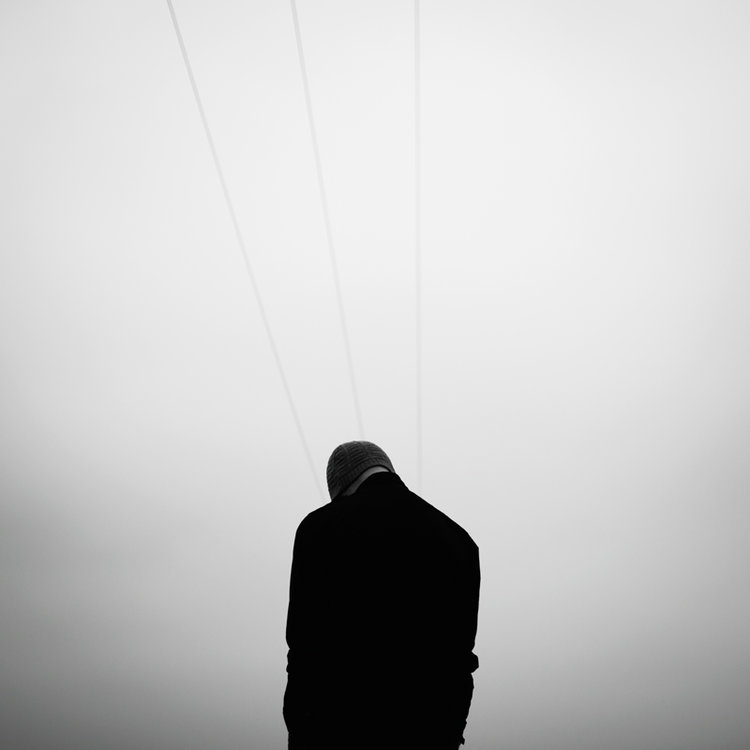

Miguel Refresco is one of the most emerging Portuguese photographers. Born in 1986 in Porto, Portugal, Miguel lives and works in Porto as a freelance photographer and photography teacher. He has a degree in Audiovisual Communication Technologies - specialization in Photography of ESMAE and Master in Contemporary Artistic Practices - FBAUP. He has developed documental works related to the issues of identity and territory that he has exhibited regularly since 2008. At the same time, he collaborates with “o Ballet Contemporâneo do Norte”, “Lovers and Lollypops” and “Capicua.” His work has been published in several publications: Vice Spain, Vice Portugal, Public, Observer, P3, Scopio Network, Terrafirma. He is a co-founder of the publishing house Álea. Lately, he's been participating in group exhibitions and opened his solo exhibition with his project "Promenade" from Balkan region in Espinho Auditorium and with a book presentation of "Menir" which is his 10 years of photography project in IPCI - Instituto de Produção Cultural e Imagem.

JK: Please tell us about your background. Where and when did you study photography? What directed you towards a photographer?

MR: When I was a teenager, I wasn’t quite sure of what I wanted to study in college. I couldn’t decide if I wanted to enter a Law School or do other things like Audiovisual Communication. Eventually, I’ve decided to take a chance on a School of Media Arts and Design (IPP) and started to study Video, Sound and Photography. But it wasn’t before I went to Barcelona as an exchange student at Centre de la Imatge i la Tecnologia Multimèdia in Terrassa that I got interested in photography as I am today. Spending a lot of time alone, I had just enough time to develop new skills and techniques and I started focusing a lot on my final graduation project. But way before that, my parents got me a camera for my 9th birthday and I started taking a lot of pictures of my friends at school and during vacations. The camera still works!

JK: Who/what inspired or influenced you the most when you were studying?

MR: Looking back after all these years, I’ll have to say that it was probably the moment where I first presented my work at college to my classmates, without even knowing the shape of a photographic series nor authorial intent.So basically the thing that influenced me the most might have been my classmates and all the projects we’ve shared with each other. And, of course, my Erasmus period in Terrassa (a 40km-distant town from Barcelona) was also important. As I told you, because I spent a lot of time by myself, I had no other distractions besides my final project. Curiously, the University was quite more focused on technique rather than on the artistic approach of photography - nevertheless, I met two great Professors who taught me a lot, introducing a great deal of ideas that still influence my work today. Before this period, I was trying out a lot of techniques and styles more focused on the photojournalism aesthetics.

JK: Tell us more about your project as photographic research of that period.

MR: By that time, I was hoping to do my final Project in a specific neighborhood in Barcelona, called Carmel. A border region of Barcelona, with an astonishing view of the city where you could see traces of the Spanish Civil War (bunkers, guns, etc). It is hard to get to that specific place and there were lots of illegal occupation too: non-licensed construction and terrible conditions as well. My first attempt was trying to talk to its people, going inside their homes and tell them about the guidelines of my project. Obviously, with a combination of apathy and aggressiveness, my proposals were constantly rejected. Eventually, I started giving up on Carmel and my work became more spontaneous, less premeditated (I was just photographing without any defined or specific goal) – I’m sure that this episode still influences the way I work on my photography series: suddenly, the work shows up and you never know when it starts nor when it finishes. This gradual discovery of my working process – well, if we can even call it a process – turned it into a more spontaneous method: my camera as a constant presence of my day and photographing whatever comes along. During my stay at Terrassa, I spent most of my day time walking. Maybe strolling around is the correct way to put it since I didn’t have any destination whatsoever on my mind. All photographs that were part of “Untitled Ruptures” had this mark, of someone who was always passing by. However, it’s not a clear mark.

JK: Tell us about your last editorial project with your new Label.

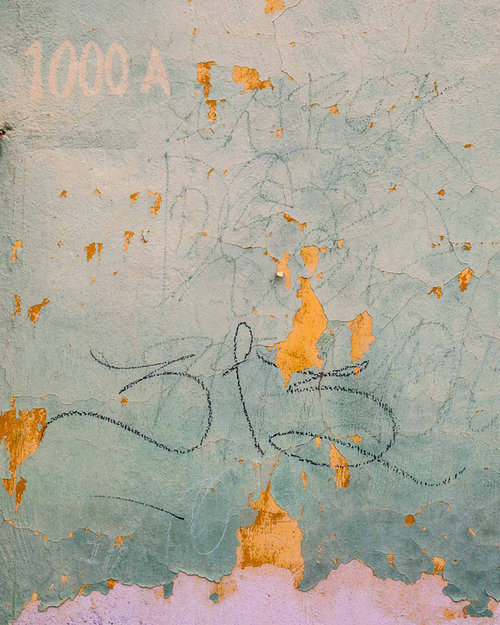

MR: Álea is an editorial project created by Daniel Costa and myself in 2016 and it was born from our desire of publishing the work of several artists we admire and follow. “Menir” seemed like a viable option for the label's first publication since we both knew it quite well and it the project was already in an advanced stage. No image in "Menir" was specifically thought to be published in a book. They are pictures that, gradually, started dialogue with each other due to little experiments for some exhibitions. Some of them determine the structure of the work - a good example of it is the opening image of the book, "Oakland" or "Greenwich" . You feel something is growing out of it and it will be hard for it to fade away. The moment where you start thinking of those pictures as a book coincides with a "subtraction stage": this means, thinking about the amount of images and trying out to delete all the obvious connections between the pages and any other kind of narrative. I get the sense that if I try to draw a narrative, I'll shut the opportunity for others to pop in and, in this book, this would be something that I was really trying to avoid. The book includes photos taken between 2006 and 2016 in several different places - from Porto, to Galiza, Cataluña and Minho region of Portugal. Despite the diversity, I link it a lot to Barcelona.

JK: I couldn't find any text or statement in your book. Is there any specific reason or intension as an author?

MR: As a matter of fact, that’s quite an interesting question since we discussed it and thought of it for months. We gave up any text whatsoever because in all of our experiments we felt that with it the book was becoming something else; its aura of the unknown stone strolling around space would vanish. All information that we decided to include was the name of the author, title and date (in the dustjacket) - and even those can be removed at any time. This was something that we came round to after several tries, there was no initial intention, but rather a consequence of all failed experiments. All information we didn’t include in the book are at the label’s website: www.aleaeditora.pt.

JK: Tell us more about your main interests. Which project are you working on? Any ideas for the future?

MR: Currently, we’re working of the distribution of the book. Personally, I’ve been focused on a project called Intermittent Fasting. It all comes down to fast for a 16-hour period and it took me to the a new project organized in volumes in which I explore a place that I’ve been just for a short time. I came up with this after a work trip to Funchal where I stayed less than 24 hours. Actually, it looks the antithesis of Menir which is built from a 10-year-old work. Up until this moment, there are three volumes: I Funchal, II Vilamoura, III Cíclades, each one with very specific formal characteristics. Three objects with very distinctive guidelines with an intention in common: at some point, they should look as a travel guide - Volume I was thought to be published as a leaflet. I like the idea of working in the immediate, without having to be stuck at a story or a long-run project; thinking of the same relevancy and legitimacy of a two-day project as a 5/10-year-old one.

JK: For which reason, you've been in those places if you didn't have any idea of the project?

MR: As I told you before, I try to include photography in my daily life, therefore I didn’t go to any of those places specifically to photograph. I went there either for professional or personal reasons. Obviously I have choices to make in those places; I know that specific zone in Vilamoura ou Funchal will be more appealing for the kind of images I do, but it’s a spontaneous decision. For this specific project - Intermittent Fasting - the less I know the better.

JK: What are your inspirations in terms of books and photographers that influence you the most? Can you recommend some book to our readers?

MR: It’s always a hard task to tell you what influences me the most because it goes way beyond books or authors. I get a lot of inspiration from the daily life, in my case music and food - that walk side by side with each other since I cook while listening to music. But also walking and riding my car inspire me a lot. Regarding photography, I guess one of the last things I’ve read was a book that gathers interviews to several artists working on photobooks, it’s called “Photography Between Covers – interview with photobook makers”. During the 70s, Tom Dugan interviewed Larry Clark, Ralph Gibson, Robert Adams, Duane Michals, among others. Actually, I now remember that Volume III of Intermittent Fasting - Cyclades has the obvious influence of “Um Adeus aos Deuses” of Rúben A.

JK: Could you refer some emerging photographers who recently interested you? And why.

MR: This week, I came across the work of two authors that I hadn’t seen in a while: Alejandra Nuñez who documented the whole catalan punk-rock scene and Joana Castelo’s work on Vietnam.

JK: You took part in various exhibitions. Any particular advice for young photographers aspiring to display and exhibit their work without drowning in the ocean of images in which we daily swim?

MR: I have no advice to give, as a matter of fact. The idea of an ocean of images is beautiful, as long as you know how to swim in it. It is something that we need to learn how to deal with. Instagram might be that ocean: a young student today has a much more critic opinion on photography than what he could have had 20 years ago - at least because you have to choose one picture among many to publish. He spent that time deciding which elements of the image will make him choose it over others and I can either be talking about a random selfie or a self aware act of a photographer. I try to be optimistic.

JK: With rapid and continuous technological change those who want to pursue a creative career must always be updated. In addition, the vast competition requires more skills to young people entering the labor market. What are the tips and suggestions you have for the younger generation? Any particular advice for the young photographers?

MR: Technology is not mandatorily connected to the evolution of photography. I can’t see such an obvious correlation: some tools help, others don’t, it’s much more about the way you decide to work. Technology is a tool that can help you materialize your ideas.

JK: How do you think the internet and everything that is connected is affecting the production and sharing of projects and images?

MR: It’s quite a complex issue, but I guess it has more advantages than disadvantages. For promotion and sharing is great and it’s cheaper. All that involves democratization and free access to tools for creation and promotion sound great and, for this, internet has been remarkable. I like the idea of sharing and if it is easier to share I like it. In the other hand, in Instagram for example, you could easily have connection with your favorite artists.

JK: Do you have any opinion about us, scopio network?

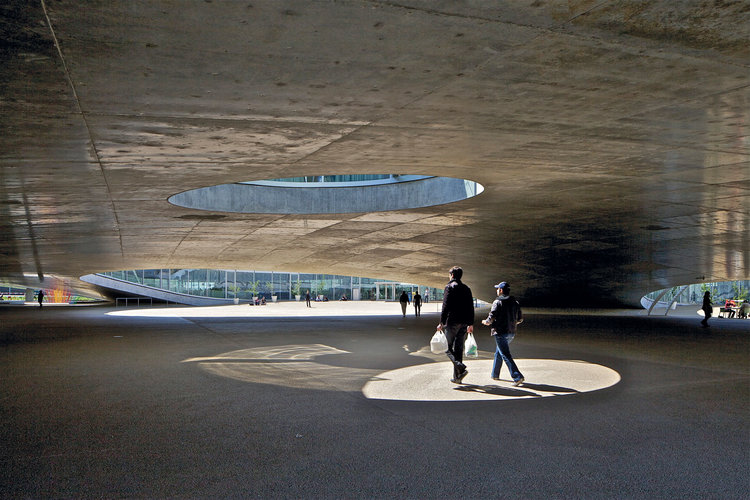

MR: I think it’s a great platform because it works such a vast area as architecture and urbanism, divided into smaller and particular branches. It’s funny that you ask that, because a few weeks ago I was reading an author project at Scopio and, two and a half hour later, I was still reading articles on the website that had nothing to do with the original topic. It’s a diverse platform, not diffusing.

* "Traversed by a meridian where time passes stumbling and guideless,“Menir” stirs Iberian geography. It is a cycle of images that doesn’t renew itself (2009 to 2016), where Miguel’s photographic gesture is swift, and the quality of testimony is less of the realm of duration, actually belonging to that of the spirits who evade the insense, errant. We leave “Menir” as we do a long day of sleepless nights. From here on, the images will be different."